Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2011 November 14

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < November 13 | << Oct | November | Dec >> | November 15 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

November 14[edit]

Direction of force in a current-carrying wire[edit]

Does the force in a single current-carrying wire point outward as the right-hand rule would seem to suggest? The force is perpendicular to the circular magnetic field lines and to the direction of the current, so it seems that two currents, whether flowing in the same direction or not, would always be pushed away from each other (or pulled towards each other, depending on how one interprets arrows pointing in opposite directions). --Melab±1 ☎ 02:30, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Does the article Right-hand rule help? --Jayron32 02:32, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- No, it doesn't. I understand what the right-hand rule says, but I cannot make the connection between that and the generated when two current-carrying wires are placed next to each other. --Melab±1 ☎ 02:41, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- It's got nothing to do with the force, the force is always outwards. It has to do with the three dimensional magnetic field lines which spiral around the conductor. In two parallel conductors flowing the same direction, the tangenial field lines of both conductors are alligned and they are attracted. When the conductors flows in opposite directions, they are repelled because the field lines oppose. Plasmic Physics (talk) 04:42, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

HIV[edit]

What percent of HIV+ people develop AIDS? Source please. CTJF83 03:37, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- The problem with any answer we could give is that anyone with HIV might eventually develop AIDS, we can't just conclude that since they haven't yet, they never will. I suppose we could dig up figures on what percentage go 10 years without developing AIDS, if that would help. Also, do you mean what percentage will develop AIDS if untreated ? StuRat (talk) 03:45, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Among HIV positive people who don't get antiretroviral treatment, virtually all (> 99.5%) will develop AIDS sometime within the 20 years following infection.[1] The picture for HIV positive people who do get antiretroviral treatment is much better (see here for example), but I can't as readily find statistics about such people expressed in terms of what fraction develop AIDS within some given time period after infection. Red Act (talk) 04:18, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Good point, StuRat, I wasn't very specific, good link Red, thank you both for the answers. CTJF83 05:39, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

Neptune and the IAU's definition of "planet"[edit]

Just so everyone knows, I'm not out to challenge the IAU's assignment of "planet" status to Neptune, but I wanted to raise a question I'm not sure anyone has considered -- Per the IAU's criterion of a planetary body having "cleared the neighborhood" of other gravitationally significant bodies in order to be considered a planet, and recognizing that Neptune's orbit crosses that of Pluto regularly, does Neptune in fact meet the IAU's definition of a planet? If so, how?

Thanks! Evanh2008, Super Genius Who am I? You can talk to me... 04:20, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Every planet has other objects which either cross their orbit similarly (consider the numerous Near-Earth objects for example) or exist nearby. Additionally, I wouldn't go so far as to consider Pluto to be "gravitationally significant" to Neptune; it is only 1/5th the size of Earth's own moon, and Neptune itself is 17 times as large as the Earth. Pluto itself is basically the largest object of the Kuiper belt which includes a whole slew of objects that exist beyond Neptune. The idea of clearing one's neighborhood is basically based on mass; an object of signficiant mass will, given enough time, have either attracted or repeled or entered into orbital resonance with or significantly influenced all other objects nearby (such as collecting them at Lagrangian points). Neptune is clearly of enough mass to do this. Neptune's neighborhood is significantly clear; compared to Pluto's which is basically the entire Kuiper Belt. One way to think of the Kuiper Belt is as a lower-density version of the Asteroid belt, and no one seriously considers large objects there, like Ceres to be planets. Part of the problem facing the IAU when it demoted Pluto was the increasingly arbitrary line they needed to draw, given that there are a lot of near-Pluto sized objects in the Kuiper Belt, and even further objects like Sedna. Pluto is really small, compared to the other 8 planets, even Mercury is 2.5 times bigger than Pluto, and Mercury doesn't exist within a big belt of objects of similar size and composition. It's a case where Pluto's initial promotion to the class of "full fledged Planet" was made early in our understanding of Astronomy, and as more knowledge of our Solar System has become known, the less wise that decision became. Yes, the line is somewhat arbitrary that excludes Pluto (and Sedna, and Makemake, and a whole bunch of other objects), but a line needs to be drawn somewhere, given the larger and larger number of objects and thus the finer and finer distinctions that needed to be drawn. The distinction that keeps Pluto out makes somewhat more sense, in our current understanding of the Solar System, than one that would put Pluto in (and also necessitate the inclusion of dozens of other objects). It's upsetting to people who, as school children, were taught that there were 9 planets and not 8, but then again these same children were taught that Columbus discovered America, that there are 5 tastes that can be mapped onto the tongue, etc. etc. --Jayron32 04:53, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Minor note: for several decades after they were discovered, Ceres and Pallas were called planets by most. It was only the discovery of the scale of the asteroid belt that ended this practice, and led to people using the previously coined term 'asteroid', even though earlier astronomers had clearly thought they could not be planets. This very closely parallels what happened with Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, with the added sting that Pluto itself was initially thought to be considerably larger, until Charon and the other 'moons' were discovered. Leave it a few decades and schoolchildren will mostly be no more able to name Pluto than they can name Ceres, let alone consider them planets. 86.163.1.168 (talk) 11:05, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- See the first paragraph Clearing the neighbourhood#Details, and Orbital resonance. PrimeHunter (talk) 05:05, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- In my day, the term "minor planets" was used as a synonym for "asteroids". And given that asteroid means "star-like", which they ain't, "minor planets" (or "dwarf" planets) is certainly a much better term. As regards Neptune and Pluto, I'm not so sure that Pluto's eccentric orbit actually intersects Neptune's roughly circular orbit. But supposing it did, and supposing the two objects arrived there at the same time someday (which is also low probability), what would likely happen? Would Neptune simply capture Pluto and its smaller companions so they would become moons? Or would something more violent happen? ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 01:44, 15 November 2011 (UTC)

- As already mentioned, Pluto and Neptune are in orbital resonance - for every three revolutions of Neptune, Pluto makes two. Their orbital positions are repeat with a period of three Neptunian years (494 Earth years). They will never collide (until something significantly interferes with the dynamics of that part of the solar system). Buddy431 (talk) 03:16, 15 November 2011 (UTC)

- Well-answered! I did some more research and discovered that, although the orbits do cross, the two bodies are projected to never collide. Thanks, all. :) Evanh2008, Super Genius Who am I? You can talk to me... 02:59, 15 November 2011 (UTC)

- To stress one point: The orbital resonance and hence the non-collision are not just accident, but the effect of Neptune's gravitational influence on Pluto. Thus, Neptune "dominates" Pluto. Of course there also is an effect in the other direction, but it is proportionally so much smaller that it can be largely ignored. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 09:53, 15 November 2011 (UTC)

- Well-answered! I did some more research and discovered that, although the orbits do cross, the two bodies are projected to never collide. Thanks, all. :) Evanh2008, Super Genius Who am I? You can talk to me... 02:59, 15 November 2011 (UTC)

The big four engineerings[edit]

Civil, mechanical, electrical and chemical are often consider the four major disciplines of engineering. Is there any logic behind the choice of these four? They just seem somewhat arbitrary to me. Widener (talk) 05:57, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- I suspect this is because historically, these were the four departments within an engineering school, other engineering programs began as a subdicipline of one of these; while some have been "spun off" as their own programs, you still find that most major universities consider these to be the "major" engineering programs. My suspicion is that these four disciplines graduate the most students and have the most programs at the most universities. Other specialties (like, say, "nuclear engineering", "marine engineering", "plastics engineering", etc.) tend to only show up at a few schools, while the "Big Four" are at nearly all schools that offer engineering majors. There is some background at Engineering#Main_branches_of_engineering and List of engineering branches, but it is limited in historical scope: It merely recognizes the existance of the four-branch classification without explaining how or why it has developed. --Jayron32 06:03, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Note that the original engineering discipline was Military engineering, and Civil engineering was subsequently so named to distinguish it. {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195} 90.197.66.147 (talk) 09:36, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- "Mechanical engineers build weapons; civil engineers build targets". AndrewWTaylor (talk) 16:04, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

Endemic v/s Endangered v/s Extinct species[edit]

dear friends, I have a query.in news papers whenever i go thru articles relating to environment and ecology,i come across 'endemic , endangered, extinct'...what exactly is the difference....recently black rhinos(which are declared as extinct) was in news....also i have a confusion: 1. difference between "PROBABLY extinct" and "POSSIBLY extinct"....white rhinos(probably extinct) and Javan rhino(probably extinct).. pls explain me,i went thru many websites..but im not clear in concept...

regards Navneeth — Preceding unsigned comment added by Navneeth tn (talk • contribs) 09:26, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- An Endemic species is a species that is found in only one area of the world. For example, Galapagos tortoises are endemic to the Galapagos islands. They are found nowhere else.

- Endangered species and Critically Endangered species are species which are very close to disappearing completely. For example, the Philippine Eagle only has around 180 to 500 individuals remaining in the wild.

- Extinct species are species which do not exist anymore. That means they're gone forever. It may be recent or it may be ancient extinctions. Examples are mammoths and Tasmanian tigers.

- There is no difference between 'Probably extinct' and 'Possibly extinct'. Both classifications mean that the animals or plants haven't been seen for some time now and are believed to have completely died out. Examples include the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, which was last seen in 1944.

- See also IUCN Red List.-- Obsidi♠n Soul 09:40, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- I think that "possibly extinct" means that the animal has not been seen in awhile, and people are considering the possibility that it might be extinct - but they don't know yet, and are not ready to say that it's extinct. "Probably extinct" is that people believe that the animal is extinct, and that there are not good chances that there are any left. Again, however, they are not quite sure, and allow for the possibility that there are still some that missed observation. The difference in meaning is fairly slight. Falconusp t c 12:35, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Could be as these are not really formal classifications, merely subjective opinion of the status. Both "possibly extinct" and "probably extinct" are still classified under Critically Endangered (CR), though 'Possibly Extinct' has been proposed as another status (no 'Probably' though). Currently, the only other formal classification between CR and definitely extinct (EX) is Extinct in the Wild (EW), where the species are known to be definitely extinct in their original habitat and now only reside in artificial populations (including zoos). Sadly most EW eventually succumb to extinction.-- Obsidi♠n Soul 13:08, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

thanks a lot dear friends for answering my queries

regards

navneeth — Preceding unsigned comment added by Navneeth tn (talk • contribs) 14:21, 15 November 2011 (UTC)

Which international agency has got the power of terming a species as "extinct" or "endangered"?[edit]

pls answer my query

- regards, navneeth — Preceding unsigned comment added by Navneeth tn (talk • contribs) 09:28, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (usually abreviated to IUCN) Roger (talk) 09:37, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

thanks a lot for all who answered me... — Preceding unsigned comment added by Navneeth tn (talk • contribs) 14:19, 15 November 2011 (UTC)

Roslyn Pliosaur find date[edit]

Stubbington (2008). "Ely master plan" (PDF). p. 2. says that Roswell Pits 1 mile (1.6 km) north-east of Ely, Cambridgeshire are "... where extraction of the Jurassic Kimmeridge Clays has exposed a remarkable series of fossils. These include a wide variety of ammonites, belemnites, bivalves, fish and even a near complete specimen of a Pliosaurus". Is this possibly a Pliosaurus brachydirus (Marr, Shipley 2010 p. 68)? How do I determine when this Ely Pliosaur was found? Has this remarkable series of fossils been listed in one place? What (if anything) is (or was at the time) remarkable here? This Ely Pliosaur is not to be confused with Stretosaurus macromerus Tarlo 1959 (Stretham is 4 miles (6.4 km) south-west of Ely). Roswell Pits have also been referred to as Roslyn pit (Marr, Thomas 1967) and as Roslyn Hole (Skertchly 1877) --Senra (Talk) 13:53, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Tough one. Doesn't help that the systematics of Pliosaurus and Plesiosaurus are currently extremely confusing. I found several references to fossils recovered from Ely. The most significant of which is the holotype specimen of what Owen initially described as Plesiosaurus brachyspondylus. This was later transferred to Pliosaurus by Seeley, 1869. This is specifically stated to be from Roswell Pit, but this consisted merely of several vertebrae not an "almost complete skeleton". However, Tarlo, 1959 refers to other material including associated skeletal remains (teeth, mandible, vertebrae, limbs and limb girdles) found in 1889-1890 also from Roswell, Ely. Tarlo, 1960 stated that these were the most complete pliosaur skeleton ever recovered from Kimmeridge Clay. It's currently catalogued in the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences as J. 35991.

- So I think it's fair enough to presume that this was the specimen that paper was talking about. However, I have no idea what the current status of P. brachyspondylus is. Our article on Pliosaurus doesn't mention it and I can not access the source to check synonymy. There's, of course, Pliosaurus macromerus (=Stretosaurus macromerus), which is very different enough that Tarlo actually assigned it to a separate genus once. P. portentificus is too new (described in 2008) to be considered for synonymy with P. brachyspondylus. That leaves us with P. brachydeirus as the apparent synonym of P. brachyspondylus. And this book does indeed claim synonymy, quote: "P. brachyspondylus has been applied to immature vertebrae of this genus from Ely in Sedgwick Museum." However, Smith, 2003 apparently recognizes both of them as valid. So... *shrugs helplessly* :(

- P.S. In response to your post below, I was actually writing this one while you wrote that LOL. I am not a paleontologist though (or a biologist even), but I do have a very strong interest in both subjects. ^-^ -- Obsidi♠n Soul 16:47, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Also, Whitaker, 1891 has a list of fossils from Kimmeridge Clay (starting on page 18, those from Ely are marked with E). However that paper is ooold though, and FSM knows how many have been reclassified since then.-- Obsidi♠n Soul 17:08, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- The above sounds enough for me. I am just attempting to ensure I carefully differentiate between any Ely Roswell/Roslyn finds and any nearby Stretham finds. A year ago, I wrote the Pliosaur section of our Stretham article, where newspaper reports and Tarlo (1959) were talking about the 1952 Pliosaur find in the Stretham coprolite pits. (Trying to) re-read Tarlo (1959) again today, I can see he mentions separate Seeley and Owen Pliosaur specimens from the Ely Roswell Pits. I might leave remarkable series in (fossils generally not just the Pliosaur) but remove near complete :) Thank you for your help --Senra (Talk) 18:42, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Ah, apologies for bogging you down with taxonomy, heh. Anyway yep. Owen described the original holotypes from the Headington Pits (not Roswell). Seeley was the one who primarily used Roswell specimens (which Tarlo used as the neotype since the holotypes have all been lost). Both however consisted only of vertebrae. Finally, Tarlo was the one to use the most complete skeleton recovered, the 1889 specimens recovered from Roswell which was previously undescribed.

- Also Tarlo actually published two papers successively in 1959 in the same journal (Palaeontology), :P The first ("Pliosaurus brachyspondylus (Owen) from the Kimeridge [sic] Clay") concerned P. brachyspondylus and the second ("Stretosaurus gen. nov., a giant pliosaur from the Kimmeridge Clay") was about P. macromerus. The latter was the paper which reassigned P. macromerus to Stretosaurus, which has now been challenged and reverted per Smith & Walton (2004)- Obsidi♠n Soul 19:25, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

Coldsores[edit]

My question is, is it true that everyone or nearly everyone already has the coldsore virus already in them ? Because when I gone to give blood the staff refuse to let me donate if I've got or show signs of a coldsore, I assume to prevent the spred of infection. But I've heard from different people (one of them being a doctor) on seperate occasions that we already got the virus in laying dormint in us & every now & then it "wakes up" giving us the coldsore. Is this true ? Scotius (talk) 13:54, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- The virus is not called the coldsore virus. It is the herpes simplex virus. Various studies have shown that about half the U.S. population has the virus by age 18. By age 50, the rate increases a lot. It is transmitted by contact with an active coldsore outbreak. So, it is obvious that many people get it when they are babies and their disease laden relatives slobber all over them. If you are lucky enough to make it past that stage, there will likely be some point in life where you will kiss someone with a coldsore. But, rate of infection has nothing to do with giving blood in general. I give blood every six weeks and there is nothing on the questionnaire about coldsores. -- kainaw™ 14:01, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

The staff in the donor clinic did state that I couldn't donate on those occasions as I had a coldsore at the time. Also the reason i was saying coldsore virus was because I didn't know the exact name at the time, thanks for reminding me though. Scotius (talk) 14:27, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Actually partially true. It's been discovered that human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) have the ability to integrate themselves into human chromosomes. As a result, the virus becomes part of the DNA and 1% of the human population become permanent carriers of the virus (every single cell of their body has the virus as part of its genetic material since birth). The most diabolical thing of this is, the viruses maintain the ability to regain its independent infectious forms.

- It's also not the only one. A lot of viruses actually coexist with their hosts without any signs of illnesses. After all, the most successful parasites are those which do not kill their carriers. A significant part of our DNA and DNA of other organisms (nearly 8% in humans) are also believed to be the remnants of past infections of viruses. They are collectively known as viral fossils, as they are often very old. Human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) in humans are examples of this. They're suspected to be the cause of some apparently "cause-less" diseases and are significant enough to actually affect evolution through insertional mutagenesis and horizontal gene transfer

- The most fascinating example in nature is perhaps polydnaviruses in insects. Polydnaviruses also become integrated into the very DNA of their hosts - parasitoid wasps. This means every wasp is automatically a carrier of the viruses at birth. However, unlike other viruses, the relationship is symbiotic. The wasps use the viruses as a sort of biological weapon and a primitive immune system, in return the viruses benefit by securing replication.

- Yeahbut....HHV-6 doesn't cause cold sores. - Nunh-huh 18:50, 15 November 2011 (UTC)

- Wow! Epic post, Obsidian. I wish you were a palaeontologist :( --Senra (Talk) 14:45, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- The Herpes simplex virus article says that the virus is ubiquitous, suggesting it's pretty hard to avoid it. However, (some pure OR here) I've experienced cold sores all my life, usually once or twice a year when I've had a cold or been otherwise run down. I've now been married to the same lovely lady for 39 year, and we have three children. None of them, wife or now adult children, have ever displayed coldsore symptoms. So, while the virus might be everywhere, coldsores aren't. Oh, and I've been a blood donor in Australia for all my adult life, and never been declined for having the virus. I guess I never turned up for a donation with obvious coldsores though. HiLo48 (talk) 17:08, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- It's not just to prevent the spread of infection (though you're certainly going to be shedding more virus particles when you have an active sore than when the infection is latent, and not everyone carries HSV). To quote Grandpa Simpson, the presence of any active infection "angries up the blood"; while you have a cold sore, your blood is likely to contain any number of inflammatory factors that we'd rather not transfuse into an already-sick individual. In general, it's best not to confuse, distract, or annoy the recipient's immune system. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 23:44, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

Saying about creationist/ID in science[edit]

I know I ran across on WikipediA a page about a USENET saying that was essentially "most 'scientists' who publicly support creationism tend to have engineering backgrounds". I can't remember the exact phrasing to find the article, does anyone know it? 76.117.247.55 (talk) 15:43, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- The talk.origins newsgroup would probably be the most likely source. Google Groups link. AndrewWTaylor (talk) 16:10, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Right, but there's an name for that particular observation (In the same way Godwin's Law has a name) and I know there was a WikipediA page describing it, it's origins, etc. Does it still exist? I can't find it with the search terms I'm using. 76.117.247.55 (talk) 16:56, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Our article was deleted, but see Salem Hypothesis over at RationalWiki. Deor (talk) 17:32, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Right, but there's an name for that particular observation (In the same way Godwin's Law has a name) and I know there was a WikipediA page describing it, it's origins, etc. Does it still exist? I can't find it with the search terms I'm using. 76.117.247.55 (talk) 16:56, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- That's it exactly. Thank you. 76.117.247.55 (talk) 22:09, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- This article (http://www.watchtower.org/e/20040622/article_01.htm) quotes The Guardian as saying that "the level of belief is highest among practitioners of the hard sciences, such as physics and geology, lower for the soft sciences, such as anthropology."

- —Wavelength (talk) 17:49, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- I've met plenty of believers in my science (Geology), but no creationists whatever (apart from one visiting undergrad from the US when I was a postgrad), not necessarily much of a correlation there. Mikenorton (talk) 18:05, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- This is one of those questions where you are likely to get different answers depending on how you phrase it.

- "Do you believe in a God that created the known universe"

- "Do you believe in the specific tenets of "creationism science" or "intelligent design" as it pertains to the manner in which the Universe came to be as it is today"

- "Do you believe literally in the creation events as described by Genesis 1 in the Christian/Hebrew Bible"

- The first will likely receive many more affirmative responses from scientists of all disciplines who are religious people. The second or third will receive much less response from scientists, and yet they all could be (over)simplified as "The number of people who believe in "creationism". They all carry some element of creationism in them, so depending on how you ask the question, you can get very different results. On poll may show that (fake random number) some 30% of scientists may believe in the first statement, while only (fake random number) 0.01% believe in the last statement. Someone who wishes to prove that scientists believe in creationism may quote the first number, while someone who wishes to ptove that scientists DONT may quote the last number. This is called "lying with statistics" and is done all the time. --Jayron32 19:07, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- This is one of those questions where you are likely to get different answers depending on how you phrase it.

- Statisticians, like all other people, have a choice in regard to being honest-hearted and open-minded about the evidence.

- —Wavelength (talk) 19:43, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- While I can understand Lewontin's idealism and I do find Dawkins annoying most of the time (Sagan more or less said the same thing in The Demon-Haunted World regarding current mainstream scientific attitudes to the "paranormal"), Lewontin makes the mistake all true atheists make: to treat "the Divine" as some sort of mashed-together superentity of different human religions. The reality is very different. Each god is as ridiculous to followers of another god as it is ridiculous to those who do not believe in gods at all. You are far more justified in accusing believers of being nonbelievers of your specific religion.

- The divine (to me, at least), is virtually the same thing as the natural world. It's mysterious and exciting and discovering it little-by-little is one step closer to knowing yourself. After all, who wouldn't want to know the meaning of it all? Who wouldn't want to finally understand why? (aside from 42) But organized religions today which claim to already know all the answers is simply not enough. A miracle is a very unnatural event and thus the farthest thing from my idea of divine. It's cheap and it's cheating. Preferring to honestly say "I don't know" or acceding to the "maybes" of science (e.g. the Big Bang, abiogenesis (not evolution which does have plenty of evidence already), the true extent and topology of the universe, the possibility of extraterrestrial life, etc.) does not automatically make you a slave to materialism. If the alternative is the rather pathetic human ideas of the divine (with the possible exception of Buddhism, which is technically a form of atheism anyway), I'd still avoid it completely no matter how inadequate the current scientific explanations may be.

- I mean, come on. If a god did exist, I wouldn't exactly be thrilled to find out that it's that bratty, jealous, vengeful, totalitarian, and suspiciously male human-like wizard of the Bible whose greatest achievements consisted merely of the creation of the Solar System; a single rather evil species; and a book which doesn't seem to talk about anything beyond the borders of the Middle East or talks about who begat who most of the time instead of something actually profound. At least give me something I could honestly be in awe of. Like a mathematical formula that explains everything, a god which can only be explained in irrational numbers, a god who promises something more than 70 virgins and an eternity of boredom, or a god who did not resort to magic tricks and threats of torture to impress people. Even now, I think, we can already recreate all the miracles of the Old Testament... ironically using science.

- The problem is not an adherence to materialism. The problem is that even the patent absurdity of some scientific constructs pale in comparison the batshit insane absurdity of an entire species punished for eating the fruit of mystery tree #1 because of a talking snake in a literal utopia where lions have fangs but eat grass and probably had a very hard time at it too (and hey grass are living things too) in a flat world with... you get the drift.

- I mostly agree, but where in the Bible does it say that the world is flat? I know that Hebrew cosmology probably had a flat Earth, but does the Bible ever say explicitly that the Earth is flat? --140.180.3.244 (talk) 06:44, 15 November 2011 (UTC)

- Mostly inferred. Several references to the "four corners of the Earth" (which non-literalist Christians today interpret as the cardinal directions not actual corners), "the edges of the Earth" (from which the wicked fall off), immovable "foundations"/"pillars", referring to it as a "circle" (i.e. a disk) with a "canopy", and a passage about the sun setting and then hurrying back to where it rose, a reference to the "length" of the earth and the "breadth" of the sea, and a very high mountain you can climb that can apparently show everything on Earth.-- Obsidi♠n Soul 07:14, 15 November 2011 (UTC)

[edit]

Do humans who live the longest tend to be shorter than average? and if so, how much shorter? and also if so, how does being shorter help you live longer? --Kenatipo speak! 16:17, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Does this article help? It took me longer to type this than to find that article using Google. --Jayron32 18:59, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- The short answer is that the larger body mass associated with increased height increases the cardiovascular load which seems to lead to a slight decrease in longevity. see Human height#Role of an individual's height for more details. Dauto (talk) 19:12, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- All else being equal, that may be true. If you compare height with longevity across the whole world population, though, then I would expect you to get the opposite result. Height is generally correlated with nutrition and health during childhood (and pregnancy), which I would expect to be correlated with longevity as well. --Tango (talk) 20:52, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Would enhanced earnings tend to be a factor translating into into enhanced longevity? Bus stop (talk) 21:28, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- It also may be necessary to distinguish between average life span and extremes of longevity. It may be that taller people have a longer median life-span, but that the oldest 1% tend to be shorter. For example, this study [2] found that tall Koreans are less likely to die during middle age than their short counterparts. On the other hand centenarians (individuals living more than 100 years) tend to smaller on average, even after accounting for the fact that people tend to shrink with age [3]. It is possible that height may be a benefit during some parts of life and a detriment during others. Dragons flight (talk) 21:56, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

Speed of Light[edit]

We are told that the speed of light is constant---that the light from an object moving away from us comes at the same speed as that from an object approaching. Yet we are told that objects moving away from us have a “red shift” from the Doppler Effect. Can you explain this contradictionOakviewmark (talk) 20:08, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- The red shift is a change in frequency, not speed. For a simplistic example, consider a star that shoots out a photon at you every second on the second. The photons hit you every second on the second. Now, start moving the star away from you. Every photon has to travel a little farther to get to you than the previous one. They are still emitted every second on the second, but you receive them with a little more than a second between them. The speed of the photons didn't change, but the frequency did. -- kainaw™ 20:16, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Kainaw's example scenario is a bit more tricky than it seems, because he's describing doppler-shift on the arrival time of a very small number of photons - which we would measure as a variation in the shot noise statistics, not the photon frequency; but the photon frequency is also doppler-shifted. Our article is the doppler effect, and it explains the mathematics very rigorously. Nimur (talk) 20:24, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

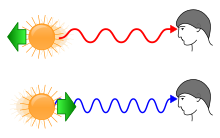

- I find this image helpful in understanding. Both the redshifted and blueshifted light are measured as travelling at the same speed, but their wavelength is squished when the light source is moving towards you, and stretched when moving away. The same is true if the light source remains stationary and you move towards or away from it. --Goodbye Galaxy (talk) 20:52, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Even with sound doppler effect, the sound still reaches you at "the speed of sound", it's just the pitch that changes, right? Vespine (talk) 23:31, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Most of the time, yes. However, sound is unlike light - the speed of sound is not a "hard limit of the universe," it's just a statistical property of air molecules. It is possible to move a source of sound faster than the sound-wave itself can propagate; this results in a transsonic shock or "sonic boom" - in other words, a breakdown of the simplistic model of sound as a linear, isotropic pressure-wave. If you move a source of sound at a nontrivial fraction of the sound velocity, the propagation becomes increasingly nonlinear, meaning that the speed of sound behaves less like a constant. For simplicity, we neglect that effect when discussing the doppler frequency shift. Nimur (talk) 23:50, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- Yeah, sound doesn't work exactly like light. If you move towards a sound source, you would measure the sound waves as coming towards you at the speed of sound + your speed. With light, the speed is always the same, no matter what. --Goodbye Galaxy (talk) 15:01, 15 November 2011 (UTC)

- Even with sound doppler effect, the sound still reaches you at "the speed of sound", it's just the pitch that changes, right? Vespine (talk) 23:31, 14 November 2011 (UTC)

- I find this image helpful in understanding. Both the redshifted and blueshifted light are measured as travelling at the same speed, but their wavelength is squished when the light source is moving towards you, and stretched when moving away. The same is true if the light source remains stationary and you move towards or away from it. --Goodbye Galaxy (talk) 20:52, 14 November 2011 (UTC)