Amazonomachy

In Greek mythology, an Amazonomachy (English translation: "Amazon battle"; plural, Amazonomachiai (Ancient Greek: Ἀμαζονομαχίαι) or Amazonomachies) is a mythological battle between the ancient Greeks and the Amazons, a nation of all-female warriors. The subject of Amazonomachies was popular in ancient Greek art and Roman art.

Amazonomachy in Myth[edit]

Throughout all of antiquity, the Amazons were regarded as a race of female warriors descended from Ares, fiercely independent and skilled in hunting, riding, archery, and warfare. They worshiped Ares and Artemis, respectively the god of war and the goddess of the hunt, and their geographic locations were notably associated with Scythia and the Asia Minor.[1]

In Greek epic narratives, the Amazons were perceived to be non-Greek heroic figures who challenged the strength and masculinity of Greek heroes on the battlefield, such as Achilles, Bellerophon, Heracles (Hercules), Theseus, and the Athenians.[1]

Trojan War, Achilles[edit]

In the lost Greek epic Aethiopis, which was published in the 8th century BCE and is widely attributed to Arctinus of Miletus, Achilles fights and kills Penthesilea, the queen of the Amazons who came to aid Troy after the death of Hector. The oral myths and retellings of this epic fall of Troy referencing the Amazons contributed to Homer's Iliad and Odyssey.[2]

Ninth Labor, Hercules[edit]

During Hercules’ ninth labor, Hercules was given the task by Eurystheus to obtain the Amazon queen Hippolyta’s beloved girdle. In some versions of this myth, Hera incites an aggressive response from the Amazons, leading to a bloody battle where the Amazons are ultimately defeated. Hippolyta was then either killed by Hercules or lived on to later become the catalyst for the Attic War between the Amazons and Athenians.[1]

Attic War, Theseus[edit]

In the versions where Queen Hippolyta survived, she would later be kidnapped and taken to Athens by Theseus, with whom she married and bore a son, Hippolytus. In other renditions, Hippolyta’s sister, typically Antiope, assumes her role in Theseus' narrative. As a result of the kidnapping, the Amazons invaded Greece, inciting the legendary Attic War between the Amazons and Athenians, which ended in the Amazons’ defeat.[3]

Symbolism of Amazonomachy[edit]

Amazonomachy represents the Greek ideal of civilization. The Amazons were portrayed as a savage and barbaric race, while the Greeks were portrayed as a civilized race of human progress. According to Bruno Snell's view of Amazonomachy:

For the Greeks, the Titanomachy and the battle against the giants remained symbols of the victory which their own world had won over a strange universe; along with the battles against the Amazons and Centaurs they continue to signalize the Greek conquest of everything barbarous, of all monstrosity and grossness.[4]

In Quintus Smyrnaeus's The Fall of Troy, Penthesilea, an Amazonian queen, who joined on the side of the Trojans during the Trojan war, was quoted at Troy, saying:

Not in strength are we inferior to men; the same our eyes, our limbs the same; one common light we see, one air we breathe; nor different is the food we eat. What then denied to us hath heaven on man bestowed?[5]

According to Josine Blok, Amazonomachy provides two different contexts in defining a Greek hero. Either the Amazons are one of the disasters from which the hero rids the country after his victory over a monster; or they are an expression of the underlying Attis motif, in which the hero shuns human sexuality in marriage and procreation.[6]

In the 5th century BC, the Achaemenid Empire of Persia began a series of invasions against Ancient Greece. Because of this, some scholars believe that on most Greek art of that time, the Persians were shown allegorically, through the figure of centaurs and Amazons.[4]

Amazonomachy in Art[edit]

Warfare was a very popular subject in Ancient Greek art, represented in grand sculptural scenes on temples but also countless Greek vases. On the whole fictional and mythical battles were preferred as subjects to the many historical ones available. Along with scenes from Homer and the Gigantomachy, a battle between the race of Giants and the Olympian gods, the Amazonomachy was a popular choice.

Later, in Roman art, there are many depictions on the sides of later Roman sarcophagi, when it became the fashion to depict elaborate reliefs of battle scenes. Scenes were also shown on mosaics. A trickle of medieval depictions increased at the Renaissance, and especially in the Baroque period.

Early Greek Shields[edit]

Early Greek art typically depicted Amazons in battle, frequently shown riding horses or wielding weapons such as bows and arrows, swords, spears, and shields. Based on existing evidence, the first indications of these female warriors entering art was in votary shields and shield decorations, with the earliest example being on a clay shield from Tiryns from around 700 B.C.[7]

Ancient Greek Pottery[edit]

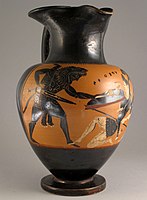

Amazons began to be featured prominently on Attic vases from around 570 BCE onward until the middle of the 5th Century. During the beginning of this time period, Amazons were most popularly depicted on Attic black-figure pottery, depicting Amazon battle scenes during the Trojan War or, more commonly, during Hercules' legendary ninth labor. Some of such vessels were inscribed with names of Amazons, with Andromache being named the most often, though none of the non-Herculean battles possessed such inscriptions. Hercules was quite often portrayed on such vessels to be in single combat against three Amazons or more.[7]

Amazons were eventually seen on red-figure pottery as black-figure pottery gradually became less popular during the advent of red-figure around the last quarter of the 6th Century. It was also around this time that Theseus also became a common feature in art depicting the Amazonomachy.[7]

Greek Architecture[edit]

Depictions of Amazon battles in Greek architecture generally fell into the category of late antique to post-classical architectural sculpture. Examples of this can be found on the west gable of the temple of Apollo at Eretria (from around the end of the 6th century BC), and on the the metopes or friezes at places such as the Athenian treasury at Delphi (490 BC), the Hephaestium at Athens (450 BC), the temple of Zeus at Olympia (460 BC), the temple of Apollo at Bassae (410 BC), the east hill at Selinunte (470 BC), the mausoleum at Halicarnassus (350 BC), and the Artemis temple in Magnesia (2nd century BC).[7]

After the Persian Wars, the Greeks attached greater significance to such battle scenes, referencing the the Attic War as a mythological example of Athens’ successful defense against foreign invaders. In particular, this Attic amazonomachy was depicted on places such as the west metope on the Parthenon (around 440 BC), shield of Athena Parthenos (around 440 BC), and in the Stoa Poikile in Athens (460 BC).[7]

West Metopes of Parthenon[edit]

Kalamis, a Greek sculptor, is attributed to designing the west metopes of the Parthenon, a temple on the Athenian Acropolis dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena.[8][9] The west metopes of the Parthenon depict a battle between Greeks and Amazons. Despite its mutilated state, scholars generally concur that the scene represents the Amazon invasion of Attica.[10]

Shield of Athena Parthenos[edit]

The shield of Athena Parthenos, sculpted by Phidias, depicts a fallen Amazon. Athena Parthenos was a massive chryselephantine sculpture of Athena, the main cult image inside the Parthenon at Athens, which is now lost, though known from descriptions and small ancient copies.[10]

Frieze in Temple of Apollo at Bassae[edit]

The Bassae Frieze, from the Temple of Apollo at Bassae, contains a number of slabs portraying Trojan Amazonomachy and Heraclean Amazonomachy. The Trojan Amazonomachy spans three blocks, displaying the eventual death of Penthesilea at the hands of Achilles. The Heraclean Amazonomachy spans eight blocks and represents the struggle of Heracles to seize the belt of the Amazon queen Hippolyta.[11]

Frieze from Mausoleum at Halicarnassus[edit]

Several sections of an Amazonomachy frieze from the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus are now in the British Museum. One part depicts Heracles grasping an Amazon by the hair, while holding a club behind his head in a striking manner. This Amazon is believed to be the Amazon queen Hippolyta. Behind Heracles is a scene of a Greek warrior clashing shields with an Amazon warrior. Another slab displays a mounted Amazon charging at a Greek, who is defending himself with a raised shield. This Greek is believed to be Theseus, who joined Heracles during his labors.

Other[edit]

Micon painted the Amazonomachy on the Stoa Poikile of the Ancient Agora of Athens, which is now lost.[12] Phidias depicted Amazonomachy on the footstool of the chryselephantine statue of Zeus at Olympia.[13]

In 2018, archaeologists discovered relief-decorated shoulder boards made from bronze that were part of a breastplate of a Greek warrior at a Celtic sacrificial place near the village of Slatina nad Bebravou in Slovakia. Deputy of director of Slovak Archaeological Institute said that it is the oldest original Greek art relic in the area of Slovakia. Researchers analyzed the pieces and determined they were once part of a relief that depicted the Amazonomachy.[14]

Roman Sarcophagi[edit]

Many representations of Amazons from the Roman times have also been found, with images of the amazonomachy included on mosaics, coins, friezes, and votive reliefs. In particular, more than 60 sarcophagus reliefs have been found to depict scenes of conflict between the Amazons and Greeks.[7]

Historical Existence of Amazonomachy[edit]

Accounts of Amazon Graves[edit]

In Athens, there were tombs of Amazons, possibly located in the Amazoneion, northwest of the Areópagos. This area was close to the ancient agora of Theseus, and the Theseion may have been nearby.[2]

Writers such as Plutarch, Kleidemos, and Pausanias cited the existence of Amazon graves and landmarks throughout Athens to be historical evidence of the Amazons’ campaign against the city. As stated in Plutarch’s Life of Theseus: “... the fact that [the Amazons] encamped virtually within the city is supported both by place names and by the graves of the fallen.”[15] Many of these writers also described the battle plans of the Amazons and Greeks based on the distribution of graves.

The grave of Antiope (Theseus’ wife) was identified by Pausanias (1.2.1) and Plutarch (Theseus 27.5) to located near the Sanctuary of Gaia in Athens. Another Amazon Molpadia was said to have been buried there as well, when both of them died during the Amazon’s invasion.[15]

According to (the Boiotian) Plutarch, Amazons that were wounded in battle with the Athenians after their failed invasion were not only buried in Athens but were also known to have fled and fought elsewhere, being buried in places such as Megara, Boiotia, Chalkis, and in Thessaly at Skotoussa and Kynoskephalai.[2][15]

Possible Historical Counterparts [edit]

As Greek civilization began to extend to areas around the Black Sea, the Greeks began to identify and associate these mythical wild and warlike foreign females with the Scythians in their artwork and literature. In particular, the Amazons were often portrayed similarly to steppe nomad horsewomen.[15] As the Greeks became more aware of steppe nomad cultures, their depictions of the Amazons in art and literature began to integrate more realistic details corresponding to the artifacts (weaponry, attire, & equipment) found in kurgans (grave mounds) of Scythians.[16]

Despite of the lack of conclusive evidence pointing to the existence of the Amazons, some modern scholars and archaeologists have claimed that such steppe nomad horsewomen could have potentially existed as the Amazons’ historical counterparts. Though their actual connection to the mythical Amazons is controversial, it is clear that such steppe warrior women did exist, as modern excavations in the 20th century have discovered more than 1,000 tombs of tribes such as the Saka-Scythians across the Eurasian steppes, of which about 300 of these burials have been identified to be those of armed warrior women (as of 2016).[16]

Gallery[edit]

-

Heracles in the battle, 6th century BC

-

Achilles killing Penthesilea. Tondo of an Attic red-figure kylix, 470–460 BC. From Vulci

-

Amazonomachy, marble sarcophagus, c. 160–170 AD, Vatican Museum

-

Amazon attacking a Barbarian, sculptural group found in the Anzio Villa, Antonian era - c. 138-192 AD, Roman copy of Greek original. Palazzo Massimo Alle Terme.

-

Relief from the ruins of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus

-

Fragments of the Amazonomachy on the west pediment of the temple of Asklepios. About 380 BC

-

Kutahya archaeological museum Amazonomachy sarcophagus 8837

-

Detail of an early 3rd-century mosaic from modern Tunisia

-

Amazon from a group of terracottas making up an Amazonomachy, c. 300 BC

-

Amazonomachy marble sarcophagus, Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki

-

15th century miniature from a Histoires de Troyes; Theseus is shown as a contemporary knight.

-

Interpretation by Rubens, 1617–18

-

one of two versions by the German Anselm Feuerbach, 1873

-

Wounded Amazon, Sosikles type. Roman copy of 5th century BC Greek original.

See also[edit]

- For discussion of such battles, see Amazons in historiography

- For the most famous Amazonomachy, see Attic War

- For representation of Amazonomachies as depicted in ancient visual art, see Amazons in art and Warfare in Ancient Greek Art

- Amazon statue types

- Centauromachy

- Gigantomachy

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Cartwright, Mark. "Amazon Women". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Dowden, Ken (1997). "The Amazons: Development and Functions". Rheinisches Museum für Philologie. 140 (2): 97–128. ISSN 0035-449X.

- ^ Mark, Harrison W. "Hippolyta". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ a b DuBois, Page (1982). Centaurs and Amazons: Women and the Pre-History of the Great Chain of Being

- ^ Quintus Smyrnaeus. "The Fall of Troy." Translated by Way. A. S. Loeb Classical Library Volume 19. London: William Heinemann, 1913.

- ^ Blok, Josine (1994). The Early Amazons: Modern and Ancient Perspectives on a Persistent Myth

- ^ a b c d e f Blok, Josine (2006). "Amazons". Brill's New Pauly Online.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Jenifer Neils (5 September 2005). The Parthenon: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-521-82093-6.

The Parthenon (Plate 1, Fig. 17) is probably the most celebrated of all Greek temples.

- ^ Jay Hambidge; Yale University. Rutherford Trowbridge Memorial Publication Fund (1924). The Parthenon and other Greek temples: their dynamic symmetry. Yale university press.

- ^ a b Castriota, David (1992). Myth, Ethos, and Actuality: Official Art in Fifth Century B.C. Athens

- ^ Cooper, Frederick (1992). The Temple of Apollo Bassitas: The Sculpture, Volume 2

- ^ "Micon | Greek artist | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ Woodard, Roger D. (January 2008). The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology. Cambridge University Press. p. 298. ISBN 978-0521607261.

- ^ a.s, Petit Press (13 May 2018). "Archaeologists find oldest Greek relic in Slovak area". spectator.sme.sk. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d Rotroff Susan & Lamberton Robert . “The Tombs of Amazons,” Approaching the Ancient Artifact : Representation, Narrative, and Function, by Avramidou, Amalia & Demetriou, Denise, 2014, Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 127-138.

- ^ a b Mayor, Adrienne. “Warrior Women: The Archaeology of Amazons.” Women in Antiquity, 2016, pp. 1–17.

Further reading[edit]

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 200, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Amazonomachy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Amazonomachy at Wikimedia Commons