Shuruppak: Difference between revisions

Ploversegg (talk | contribs) →Archaeology: sm detail, ref |

Eric Kvaalen (talk | contribs) Moved some paragraphs and added some more from Schmidt's account. |

||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

'''Shuruppak''' ({{lang-sux|{{cuneiform|𒋢𒆳𒊒𒆠}}}} {{transl|sux|''Šuruppag''<sup>[[KI (cuneiform)|KI]]</sup>}}, "the healing place"), modern '''Tell Fara''', was an ancient [[Sumer]]ian city situated about 55 kilometres (35 mi) south of [[Nippur]] on the banks of the [[Euphrates]] in [[Iraq]]'s [[Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate]]. Shuruppak was dedicated to [[Ninlil]], also called Sud, the goddess of grain and the air.<ref name="Jacobsen1987">{{cite book|author=Jacobsen, Thorkild|title=The Harps that Once--: Sumerian Poetry in Translation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=L-BI0h41yCEC&q=Shuruppak+Ansud|date=1 January 1987|publisher=Yale University Press|isbn=978-0-300-07278-5}}</ref> |

'''Shuruppak''' ({{lang-sux|{{cuneiform|𒋢𒆳𒊒𒆠}}}} {{transl|sux|''Šuruppag''<sup>[[KI (cuneiform)|KI]]</sup>}}, "the healing place"), modern '''Tell Fara''', was an ancient [[Sumer]]ian city situated about 55 kilometres (35 mi) south of [[Nippur]] on the banks of the [[Euphrates]] in [[Iraq]]'s [[Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate]]. Shuruppak was dedicated to [[Ninlil]], also called Sud, the goddess of grain and the air.<ref name="Jacobsen1987">{{cite book|author=Jacobsen, Thorkild|title=The Harps that Once--: Sumerian Poetry in Translation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=L-BI0h41yCEC&q=Shuruppak+Ansud|date=1 January 1987|publisher=Yale University Press|isbn=978-0-300-07278-5}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | The city expanded to its greatest extent at the end of the Early Dynastic III period (2600 BC to 2350 BC) when it covered about 100 hectares. At this stage it was destroyed by a fire which baked the clay tablets and mudbrick walls, which then survived for millennia.<ref>{{cite book |first=Gwendolyn |last=Leick |title=Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City |location=London |publisher=Penguin |year=2002 |isbn=0-14-026574-0 }}</ref> |

||

"Shuruppak" is sometimes also the name of a king of the city, legendary survivor of [[Flood story|the Flood]], and supposed author of the [[Instructions of Shuruppak]]". |

|||

==Shuruppak and its environment== |

==Shuruppak and its environment== |

||

Shuruppak is located in [[Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate]], approximately 55 kilometres (35 mi) south of [[Nippur]]. The site |

Shuruppak is located in [[Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate]], approximately 55 kilometres (35 mi) south of [[Nippur]]. The site extends about a kilometer from north to south. The total area is about 120 hectares, with about 35 hectares of the mound being more than 3 meters above the surrounding plain, with a maximum of 9 meters. |

||

==Archaeology== |

==Archaeology== |

||

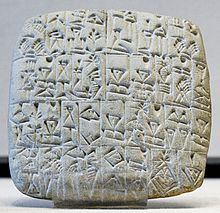

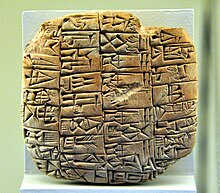

[[File:List of titles of different occupations, clay tablet from Shuruppak, Southern Mesopotamia, Iraq, on display in the Pergamon Museum.jpg|thumb|List of titles of different occupations, clay tablet from Shuruppak, Iraq. 2nd half of the 3rd millennium BCE. Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin]] |

[[File:List of titles of different occupations, clay tablet from Shuruppak, Southern Mesopotamia, Iraq, on display in the Pergamon Museum.jpg|thumb|List of titles of different occupations, clay tablet from Shuruppak, Iraq. 2nd half of the 3rd millennium BCE. Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin]] |

||

[[File:Pig-shaped rattle from Shuruppak, Iraq. Baked clay. Early Dynastic period, 2500-2350 BCE. Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Germany.jpg|thumb|left|Pig-shaped rattle from Shuruppak, Iraq. Baked clay. Early Dynastic period, 2500-2350 BCE. Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin]] |

[[File:Pig-shaped rattle from Shuruppak, Iraq. Baked clay. Early Dynastic period, 2500-2350 BCE. Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Germany.jpg|thumb|left|Pig-shaped rattle from Shuruppak, Iraq. Baked clay. Early Dynastic period, 2500-2350 BCE. Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin]] |

||

After a brief survey by [[Hermann Volrath Hilprecht]] in 1900, it was first excavated in 1902 by [[Robert Koldewey]] and [[Friedrich Delitzsch]] of the [[Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft|German Oriental Society]] for eight months.<ref>{{cite book |editor-first=Ernst |editor-last=Heinrich |editor2-first=Walter |editor2-last=Andrae |title=Fara, Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft in Fara und Abu Hatab |location=Berlin |publisher=Staatliche Museen zu Berlin |year=1931 }}</ref> Among other finds, hundreds of [[Early Dynastic Period (Mesopotamia)|Early Dynastic]] tablets were collected, which ended up in the Berlin Museum and the Istanbul Museum. In March and April 1931, a joint team of the [[American Schools of Oriental Research]] and the [[University of Pennsylvania]] excavated Shuruppak for a further six week season, with [[Erich Schmidt (archaeologist)|Erich Schmidt]] as director and with epigraphist [[Samuel Noah Kramer]].<ref name=":0">{{cite journal |first=Erich |last=Schmidt |title=Excavations at Fara, 1931 |journal=University of Pennsylvania's Museum Journal |volume=2 |pages=193–217 |year=1931 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |first=Samuel N. |last=Kramer |title=New Tablets from Fara |journal=[[Journal of the American Oriental Society]] |volume=52 |issue=2 |pages=110–132 |year=1932 |doi=10.2307/593166 |jstor=593166 }}</ref> The excavation recovered 87 tablets and fragments—mostly from pre-Sargonic times—biconvex, and unbaked. In 1973, a three-day surface survey of the site was conducted by Harriet P. Martin. Consisting mainly of pottery shard collection, the survey confirmed that Shuruppak dates at least as early as the [[Jemdet Nasr period]], expanded greatly in the [[Early Dynastic Period (Mesopotamia)|Early Dynastic period]], and was also an element of the [[Akkadian Empire]] and the [[Third Dynasty of Ur]].<ref>{{cite journal |first=Harriet P. |last=Martin |title=Settlement Patterns at Shuruppak |journal=[[Iraq (journal)|Iraq]] |volume=45 |issue=1 |pages=24–31 |year=1983 |doi=10.2307/4200173 |jstor=4200173 |s2cid=130046037 }}</ref> A surface survey was conducted in 2016 to 2018.<ref>Otto, A., & Einwag, B., "The survey at Fara - Šuruppak 2016-2018", In Otto, A., Herles, M., Kaniuth, K., Korn, L., & Heidenreich, A. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 11th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Vol. 2. Wiesbaden, pp. 293–306. Harrassowitz Verlag, 2020</ref> |

After a brief survey by [[Hermann Volrath Hilprecht]] in 1900, it was first excavated in 1902 by [[Robert Koldewey]] and [[Friedrich Delitzsch]] of the [[Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft|German Oriental Society]] for eight months.<ref>{{cite book |editor-first=Ernst |editor-last=Heinrich |editor2-first=Walter |editor2-last=Andrae |title=Fara, Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft in Fara und Abu Hatab |location=Berlin |publisher=Staatliche Museen zu Berlin |year=1931 }}</ref> Among other finds, hundreds of [[Early Dynastic Period (Mesopotamia)|Early Dynastic]] tablets were collected, which ended up in the Berlin Museum and the Istanbul Museum. In March and April 1931, a joint team of the [[American Schools of Oriental Research]] and the [[University of Pennsylvania]] excavated Shuruppak for a further six week season, with [[Erich Schmidt (archaeologist)|Erich Schmidt]] as director and with epigraphist [[Samuel Noah Kramer]].<ref name=":0">{{cite journal |first=Erich |last=Schmidt |title=Excavations at Fara, 1931 |url=https://www.penn.museum/sites/journal/9356/|journal=University of Pennsylvania's Museum Journal |volume=2 |pages=193–217 |year=1931 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |first=Samuel N. |last=Kramer |title=New Tablets from Fara |journal=[[Journal of the American Oriental Society]] |volume=52 |issue=2 |pages=110–132 |year=1932 |doi=10.2307/593166 |jstor=593166 }}</ref> The excavation recovered 87 tablets and fragments—mostly from pre-Sargonic times—biconvex, and unbaked. In 1973, a three-day surface survey of the site was conducted by Harriet P. Martin. Consisting mainly of pottery shard collection, the survey confirmed that Shuruppak dates at least as early as the [[Jemdet Nasr period]], expanded greatly in the [[Early Dynastic Period (Mesopotamia)|Early Dynastic period]], and was also an element of the [[Akkadian Empire]] and the [[Third Dynasty of Ur]].<ref>{{cite journal |first=Harriet P. |last=Martin |title=Settlement Patterns at Shuruppak |journal=[[Iraq (journal)|Iraq]] |volume=45 |issue=1 |pages=24–31 |year=1983 |doi=10.2307/4200173 |jstor=4200173 |s2cid=130046037 }}</ref> A surface survey was conducted in 2016 to 2018.<ref>Otto, A., & Einwag, B., "The survey at Fara - Šuruppak 2016-2018", In Otto, A., Herles, M., Kaniuth, K., Korn, L., & Heidenreich, A. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 11th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Vol. 2. Wiesbaden, pp. 293–306. Harrassowitz Verlag, 2020</ref> |

||

Recently a full magnetometer survey of the site was completed. The researchers found thousands of robber holes left by looters which had disturbed surface in many places. They were able to use remains of the 900 meter long trench left by excavators in 1902 and 1903 to orient old excavation documents and aerial mapping with their geomagnetic results. Part of the site was inaccessible because of the spoil heaps from the excavations. A city wall was found (in Area A), which had been missed in the past.<ref>Otto, A., Einwag, B., Al-Hussainy, A., Jawdat, J. A. H., Fink, C., & Maaß, H., "Destruction and looting of archaeological sites betweenFara/ˇSuruppak and Iˇsan Bahrīyat/Isin damage assessment during the Fara Regional Survey Project FARSUP", Sumer,64, pp. 35–48, 2018</ref><ref>{{cite journal | doi=10.1002/arp.1878 | title=Revisiting Fara: Comparison of merged prospection results of diverse magnetometers with the earliest excavations in ancient Šuruppak from 120 years ago | year=2022 | last1=Hahn | first1=Sandra E. | last2=Fassbinder | first2=Jörg W. E. | last3=Otto | first3=Adelheid | last4=Einwag | first4=Berthold | last5=Al‐Hussainy | first5=Abbas Ali | journal=Archaeological Prospection | volume=29 | issue=4 | pages=623–635 | s2cid=252827382 }}</ref> A harbor and quay were also found.<ref>[https://macau.uni-kiel.de/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/macau_derivate_00004683/kiel-up_978-3-928794-83-1_p7.pdf]Fassbinder, Jörg, Sandra Hahn, and Marco Wolf, "Prospecting in the marshland: the Sumerian city Fara-Šuruppak (Iraq)", Advances in On-and Offshore Archaeological Prospection: Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Archaeological Prospection, 2023</ref> |

Recently a full magnetometer survey of the site was completed. The researchers found thousands of robber holes left by looters which had disturbed surface in many places. They were able to use remains of the 900 meter long trench left by excavators in 1902 and 1903 to orient old excavation documents and aerial mapping with their geomagnetic results. Part of the site was inaccessible because of the spoil heaps from the excavations. A city wall was found (in Area A), which had been missed in the past.<ref>Otto, A., Einwag, B., Al-Hussainy, A., Jawdat, J. A. H., Fink, C., & Maaß, H., "Destruction and looting of archaeological sites betweenFara/ˇSuruppak and Iˇsan Bahrīyat/Isin damage assessment during the Fara Regional Survey Project FARSUP", Sumer,64, pp. 35–48, 2018</ref><ref>{{cite journal | doi=10.1002/arp.1878 | title=Revisiting Fara: Comparison of merged prospection results of diverse magnetometers with the earliest excavations in ancient Šuruppak from 120 years ago | year=2022 | last1=Hahn | first1=Sandra E. | last2=Fassbinder | first2=Jörg W. E. | last3=Otto | first3=Adelheid | last4=Einwag | first4=Berthold | last5=Al‐Hussainy | first5=Abbas Ali | journal=Archaeological Prospection | volume=29 | issue=4 | pages=623–635 | s2cid=252827382 }}</ref> A harbor and quay were also found.<ref>[https://macau.uni-kiel.de/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/macau_derivate_00004683/kiel-up_978-3-928794-83-1_p7.pdf]Fassbinder, Jörg, Sandra Hahn, and Marco Wolf, "Prospecting in the marshland: the Sumerian city Fara-Šuruppak (Iraq)", Advances in On-and Offshore Archaeological Prospection: Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Archaeological Prospection, 2023</ref> |

||

| Line 72: | Line 76: | ||

Shuruppak became a grain storage and distribution city and had more silos than any other Sumerian city. The earliest excavated levels at Shuruppak date to the Jemdet Nasr period about 3000 BC; it was abandoned shortly after 2000 BC. [[Erich Schmidt (archaeologist)|Erich Schmidt]] found one Isin-Larsa cylinder seal and several pottery plaques which may date to early in the second millennium BC.<ref>{{cite book |first=Harriet P. |last=Martin |title=FARA: A reconstruction of the Ancient Mesopotamian City of Shuruppak |location=Birmingham, UK |publisher=Chris Martin & Assoc. |year=1988 |isbn=0-907695-02-7 |at=p. 44, p. 117 and seal no. 579 }}</ref> Surface finds are predominantly Early Dynastic.<ref>{{cite book |first=Robert McC. |last=Adams |title=Heartland of Cities |location=Chicago |publisher=University of Chicago Press |year=1981 |isbn=0-226-00544-5 |at=Fig. 33 compared with Fig. 21 }}</ref> |

Shuruppak became a grain storage and distribution city and had more silos than any other Sumerian city. The earliest excavated levels at Shuruppak date to the Jemdet Nasr period about 3000 BC; it was abandoned shortly after 2000 BC. [[Erich Schmidt (archaeologist)|Erich Schmidt]] found one Isin-Larsa cylinder seal and several pottery plaques which may date to early in the second millennium BC.<ref>{{cite book |first=Harriet P. |last=Martin |title=FARA: A reconstruction of the Ancient Mesopotamian City of Shuruppak |location=Birmingham, UK |publisher=Chris Martin & Assoc. |year=1988 |isbn=0-907695-02-7 |at=p. 44, p. 117 and seal no. 579 }}</ref> Surface finds are predominantly Early Dynastic.<ref>{{cite book |first=Robert McC. |last=Adams |title=Heartland of Cities |location=Chicago |publisher=University of Chicago Press |year=1981 |isbn=0-226-00544-5 |at=Fig. 33 compared with Fig. 21 }}</ref> |

||

==Flood== |

|||

The report of the 1930s excavation mentions a layer of flood deposits at the end of the Jemdet Nasr period at Shuruppak.<ref name=":0" /> |

The report of the 1930s excavation mentions a layer of flood deposits at the end of the [[Jemdet Nasr]] period at Shuruppak. Shuruppak in Mesopotamian legend is one of the "antediluvian" cities and the home of King [[Uta-napishtim]], who survives the flood by making a boat beforehand. The [[flood story]] of the Bible, Schmidt wrote,<ref name=":0" />{{quote|seems to be based on a very real event or a series of such, as suggested by the existence at [[Ur]], at [[Kish (Sumer)|Kish]], and now at Fara, of inundation deposits, which accumulated on top of human inhabitation. There is finally “the [[Noah]] story,” which may possibly symbolize the survival of the Sumerian culture and the end of the [[Elamite]] Jemdet Nasr culture.}} The deposit is like that deposited by [[Avulsion (river)|river avulsions]], a process that was common in the [[Tigris–Euphrates river system]].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Morozova|first=Galina S.|date=2005|title=A review of Holocene avulsions of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and possible effects on the evolution of civilizations in lower Mesopotamia|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/gea.20057|journal=Geoarchaeology|language=en|volume=20|issue=4|pages=401–423|doi=10.1002/gea.20057|s2cid=129452555 |issn=0883-6353}}</ref><ref name=HalloSimpson>{{cite book |last1=[[William W. Hallo]] and [[William Kelly Simpson]] |title=The Ancient Near East: A History |date=1971}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Two possible kings of Shuruppak are mentioned in [[epigraphic data]] from later sources found elsewhere. In some versions of the ''[[Sumerian King List]]'' a king [[Ubara-Tutu]] is listed as the ruler of Shuruppak and the last king "before the flood". In the ''[[Epic of Gilgamesh]]'', a man named [[Utanapishtim]], son of Ubara-Tutu, is noted to be king of Shuruppak. The names [[Ziusudra]] and [[Atrahasis]] are also associated with him. These figures have not been supported by archaeological finds and may well be mythical. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Several objects made of [[arsenical copper]] were found in Shuruppak/Fara dating from the mid-fourth to early third millennium BC (approximately Jamdat Nasr period), which is quite early for Mesopotamia. Similar objects were also found at [[Tepe Gawra]] (levels XII-VIII).<ref>Daniel T. Potts, [https://books.google.com/books?id=OdZS9gBu4KwC&pg=PA167 ''Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations.''] Cornell University Press, 1997 {{ISBN|0801433398}} p167</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The city expanded to its greatest extent at the end of the Early Dynastic III period (2600 BC to 2350 BC) when it covered about 100 hectares. At this stage it was destroyed by a fire which baked the clay tablets and mudbrick walls, which then survived for millennia.<ref>{{cite book |first=Gwendolyn |last=Leick |title=Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City |location=London |publisher=Penguin |year=2002 |isbn=0-14-026574-0 }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Several objects made of [[arsenical copper]] were found in Shuruppak/Fara dating from the mid-fourth to early third millennium BC (approximately Jamdat Nasr period), which is quite early for Mesopotamia. Similar objects were also found at [[Tepe Gawra]] (levels XII-VIII).<ref>Daniel T. Potts, [https://books.google.com/books?id=OdZS9gBu4KwC&pg=PA167 ''Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations.''] Cornell University Press, 1997 {{ISBN|0801433398}} p167</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Two possible kings of Shuruppak are mentioned in [[epigraphic data]] from later sources found elsewhere. In some versions of the ''[[Sumerian King List]]'' a king [[Ubara-Tutu]] is listed as the ruler of Shuruppak and the last king "before the flood". In the ''[[Epic of Gilgamesh]]'', a man named [[Utanapishtim]] |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 10:58, 26 August 2023

| |

| Alternative name | Tell Fara |

|---|---|

| Location | Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq |

| Region | Sumer |

| Coordinates | 31°46′39″N 45°30′35″E / 31.77750°N 45.50972°E |

| Type | archaeological site, human settlement |

| Area | 120 hectare |

| Height | 9 metre |

| History | |

| Periods | Jemdet Nasr period, Early Dynastic period, Akkad period, Ur III period |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1902; 1931 |

| Archaeologists | Robert Koldewey, Friedrich Delitzsch, Erich Schmidt, Harriet P. Martin |

Shuruppak (Sumerian: 𒋢𒆳𒊒𒆠 ŠuruppagKI, "the healing place"), modern Tell Fara, was an ancient Sumerian city situated about 55 kilometres (35 mi) south of Nippur on the banks of the Euphrates in Iraq's Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate. Shuruppak was dedicated to Ninlil, also called Sud, the goddess of grain and the air.[1]

The city expanded to its greatest extent at the end of the Early Dynastic III period (2600 BC to 2350 BC) when it covered about 100 hectares. At this stage it was destroyed by a fire which baked the clay tablets and mudbrick walls, which then survived for millennia.[2]

"Shuruppak" is sometimes also the name of a king of the city, legendary survivor of the Flood, and supposed author of the Instructions of Shuruppak".

Shuruppak and its environment

Shuruppak is located in Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, approximately 55 kilometres (35 mi) south of Nippur. The site extends about a kilometer from north to south. The total area is about 120 hectares, with about 35 hectares of the mound being more than 3 meters above the surrounding plain, with a maximum of 9 meters.

Archaeology

After a brief survey by Hermann Volrath Hilprecht in 1900, it was first excavated in 1902 by Robert Koldewey and Friedrich Delitzsch of the German Oriental Society for eight months.[3] Among other finds, hundreds of Early Dynastic tablets were collected, which ended up in the Berlin Museum and the Istanbul Museum. In March and April 1931, a joint team of the American Schools of Oriental Research and the University of Pennsylvania excavated Shuruppak for a further six week season, with Erich Schmidt as director and with epigraphist Samuel Noah Kramer.[4][5] The excavation recovered 87 tablets and fragments—mostly from pre-Sargonic times—biconvex, and unbaked. In 1973, a three-day surface survey of the site was conducted by Harriet P. Martin. Consisting mainly of pottery shard collection, the survey confirmed that Shuruppak dates at least as early as the Jemdet Nasr period, expanded greatly in the Early Dynastic period, and was also an element of the Akkadian Empire and the Third Dynasty of Ur.[6] A surface survey was conducted in 2016 to 2018.[7]

Recently a full magnetometer survey of the site was completed. The researchers found thousands of robber holes left by looters which had disturbed surface in many places. They were able to use remains of the 900 meter long trench left by excavators in 1902 and 1903 to orient old excavation documents and aerial mapping with their geomagnetic results. Part of the site was inaccessible because of the spoil heaps from the excavations. A city wall was found (in Area A), which had been missed in the past.[8][9] A harbor and quay were also found.[10]

Occupation history

Shuruppak became a grain storage and distribution city and had more silos than any other Sumerian city. The earliest excavated levels at Shuruppak date to the Jemdet Nasr period about 3000 BC; it was abandoned shortly after 2000 BC. Erich Schmidt found one Isin-Larsa cylinder seal and several pottery plaques which may date to early in the second millennium BC.[11] Surface finds are predominantly Early Dynastic.[12]

Flood

The report of the 1930s excavation mentions a layer of flood deposits at the end of the Jemdet Nasr period at Shuruppak. Shuruppak in Mesopotamian legend is one of the "antediluvian" cities and the home of King Uta-napishtim, who survives the flood by making a boat beforehand. The flood story of the Bible, Schmidt wrote,[4]

seems to be based on a very real event or a series of such, as suggested by the existence at Ur, at Kish, and now at Fara, of inundation deposits, which accumulated on top of human inhabitation. There is finally “the Noah story,” which may possibly symbolize the survival of the Sumerian culture and the end of the Elamite Jemdet Nasr culture.

The deposit is like that deposited by river avulsions, a process that was common in the Tigris–Euphrates river system.[13][14]

Two possible kings of Shuruppak are mentioned in epigraphic data from later sources found elsewhere. In some versions of the Sumerian King List a king Ubara-Tutu is listed as the ruler of Shuruppak and the last king "before the flood". In the Epic of Gilgamesh, a man named Utanapishtim, son of Ubara-Tutu, is noted to be king of Shuruppak. The names Ziusudra and Atrahasis are also associated with him. These figures have not been supported by archaeological finds and may well be mythical.

Metalwork

Several objects made of arsenical copper were found in Shuruppak/Fara dating from the mid-fourth to early third millennium BC (approximately Jamdat Nasr period), which is quite early for Mesopotamia. Similar objects were also found at Tepe Gawra (levels XII-VIII).[15]

See also

Notes

- ^ Jacobsen, Thorkild (1 January 1987). The Harps that Once--: Sumerian Poetry in Translation. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07278-5.

- ^ Leick, Gwendolyn (2002). Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-026574-0.

- ^ Heinrich, Ernst; Andrae, Walter, eds. (1931). Fara, Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft in Fara und Abu Hatab. Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

- ^ a b Schmidt, Erich (1931). "Excavations at Fara, 1931". University of Pennsylvania's Museum Journal. 2: 193–217.

- ^ Kramer, Samuel N. (1932). "New Tablets from Fara". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 52 (2): 110–132. doi:10.2307/593166. JSTOR 593166.

- ^ Martin, Harriet P. (1983). "Settlement Patterns at Shuruppak". Iraq. 45 (1): 24–31. doi:10.2307/4200173. JSTOR 4200173. S2CID 130046037.

- ^ Otto, A., & Einwag, B., "The survey at Fara - Šuruppak 2016-2018", In Otto, A., Herles, M., Kaniuth, K., Korn, L., & Heidenreich, A. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 11th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Vol. 2. Wiesbaden, pp. 293–306. Harrassowitz Verlag, 2020

- ^ Otto, A., Einwag, B., Al-Hussainy, A., Jawdat, J. A. H., Fink, C., & Maaß, H., "Destruction and looting of archaeological sites betweenFara/ˇSuruppak and Iˇsan Bahrīyat/Isin damage assessment during the Fara Regional Survey Project FARSUP", Sumer,64, pp. 35–48, 2018

- ^ Hahn, Sandra E.; Fassbinder, Jörg W. E.; Otto, Adelheid; Einwag, Berthold; Al‐Hussainy, Abbas Ali (2022). "Revisiting Fara: Comparison of merged prospection results of diverse magnetometers with the earliest excavations in ancient Šuruppak from 120 years ago". Archaeological Prospection. 29 (4): 623–635. doi:10.1002/arp.1878. S2CID 252827382.

- ^ [1]Fassbinder, Jörg, Sandra Hahn, and Marco Wolf, "Prospecting in the marshland: the Sumerian city Fara-Šuruppak (Iraq)", Advances in On-and Offshore Archaeological Prospection: Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Archaeological Prospection, 2023

- ^ Martin, Harriet P. (1988). FARA: A reconstruction of the Ancient Mesopotamian City of Shuruppak. Birmingham, UK: Chris Martin & Assoc. p. 44, p. 117 and seal no. 579. ISBN 0-907695-02-7.

- ^ Adams, Robert McC. (1981). Heartland of Cities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Fig. 33 compared with Fig. 21. ISBN 0-226-00544-5.

- ^ Morozova, Galina S. (2005). "A review of Holocene avulsions of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and possible effects on the evolution of civilizations in lower Mesopotamia". Geoarchaeology. 20 (4): 401–423. doi:10.1002/gea.20057. ISSN 0883-6353. S2CID 129452555.

- ^ William W. Hallo and William Kelly Simpson (1971). The Ancient Near East: A History.

- ^ Daniel T. Potts, Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations. Cornell University Press, 1997 ISBN 0801433398 p167

References

- Andrae, W., "Aus einem Berichte W. Andrae's über seineExkursion von Fara nach den südbabylonischen Ruinenstätten(TellǏd, Jǒcha und Hamam)", Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft,16, pp. 16–24, 1902 (in german)

- Andrae, W., "Die Umgebung von Fara und Abu Hatab (Fara,Bismaja, Abu Hatab, Hˇetime, Dschidr und Juba’i)", Mitteilungen derDeutschen Orient-Gesellschaft,16, pp. 24–30, 1902 (in german)

- Andrae, W., "Ausgrabungen in Fara und Abu Hatab. Bericht über dieZeit vom 15. August 1902 bis 10. Januar 1903", Mitteilungen derDeutschen Orient-Gesellschaft,17, pp.4–35, 1903 (in german)

- Koldewey, R., "Acht Briefe Dr. Koldewey's (teilweise im Auszug)(Babylon, Fara und Abu Hatab)", Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft,15, pp. 6–24, 1902 (in german)

- Koldewey, R., "Auszug aus fünf Briefen Dr. Koldewey's (Babylon,Fara und Abu Hatab)", Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft,16, pp. 8–15, 1902 (in german)

- Matthews, R. J. (1991). "Fragments of Officialdom from Fara". Iraq. 53: 1–15. doi:10.2307/4200331. JSTOR 4200331. S2CID 164100986.

- Nöldeke, A., "Die Rückkehr unserer Expedition aus Fara", Mitteilun-gen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft,17, pp. 35–44, 1903 (in german)

- Pomponio, Francesco; Visicato, Giuseppe; Westenholz, Aage; Martin, Harriet P. (2001). The Fara Tablets in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. CDL Press. ISBN 1-883053-66-8.

- Wencel, M. M., "New radiocarbon dates from southern Mesopotamia (Fara and Ur)", Iraq, 80, pp. 251-261, 2018